March 24, 2017

Why does The Marshall Project’s ‘The Next to Die’ collaborative data initiative work so well? It’s easy.

For the last several months I’ve studied national and local news partnerships on behalf of the Center for Cooperative Media, as part of a project funded by Democracy Fund and the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation. Previous posts covered ways local and national newsrooms can partner right now, hurdles and opportunities for locals, and how national newsrooms can be better collaborators.

Next, we’ll look at how one smart partnership works.

Tom Meagher, the deputy managing editor of The Marshall Project, has engaged in collaborative projects with a who’s-who of national news brands: The New York Times, the Washington Post, NPR, the Guardian.

As for local partnerships? A lot of squeeze, not a lot of juice.

Generally speaking, the process to conceptualize a project is slower, editing takes longer and, once published, there’s less promotion. It can be even harder with newspapers trying to figure out the Internet, he said.

But Meagher and his team at The Marshall Project, the innovative nonprofit criminal justice site, are on to something.

Tom Meagher, deputy managing editor at The Marshall Project

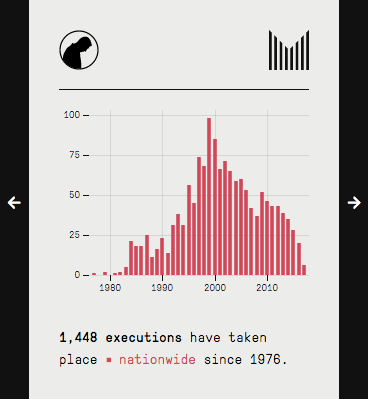

The Next to Die project has a relatively simple goal: To create a single database of upcoming executions from 10 states (there are 30-plus states with capital punishment laws on the books, but a smaller subset actually do it) and make it easy to search, sort and share.

It was conceived in 2015 by Meagher and The Marshall Project’s former managing editor, Gabriel Dance, along with others throughout the newsroom. It launched in September that year, just before Oklahoma was scheduled to execute Richard Glossip. Of the 10 states with data, The Next to Die project has partnered with local news organizations in eight of them: The Houston Chronicle, Tampa Bay Times, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Virginian-Pilot, The Frontier (Tulsa), St. Louis Public Radio, AL.com, and Cleveland.com.

What makes this concept work where others have struggled? To put it simply: The Marshall Project makes it easy.

1. It starts with good relationships, based on shared values and skills (in this case, data reporting)

Meagher said he wanted to find people “who are invested in watchdog reporting and appealing to their idealistic journalistic self.” All of them were approached either through existing relationships or through contacts at Investigative Reporters and Editors. And all had a shared interest in putting a spotlight on capital punishment and a shared sensibility about good data journalism.

“As impartial news organizations, The Marshall Project and its journalistic partners do not take a stance on the morality of capital punishment, but we do see a need for better reporting on a punishment that so divides Americans. Whether you believe that execution is a fitting way for society to deplore the most heinous crimes, or that it is too expensive, racially biased and subject to lethal error, you should be prepared to look it in the face.” Learn more here.

2. The relationship is low-friction

The concept was modeled after Homicide Watch in Washington, D.C., a community-driven reporting project that, among other things, tracks murder cases. Meagher and team provide an easy-to-use tool for inputting data, making it easy for The Marshall Project to get structured data and making life easier for local partners. “If you’re a courts reporter in a state, you probably have all the information we’re asking for or you can easily get it,” Meagher said. “So we try not to ask them to go out looking for something else.”

“The tool was well designed and the guidelines were clear,” said Lise Olsen, the deputy investigations editor and a senior reporter at the Houston Chronicle. Texas, of course, has plenty of reporting to do on the death penalty, and had a dedicated reporter assigned to the beat for years. “We do most of the reporting that it requires anyway so it hasn’t been burdensome,” she said.

3. Local partners get content (and tools) they wouldn’t otherwise have

In addition to the internal data-entry tool, which saves time and energy for some partners, The Marshall Project also provides a Next to Die widget for partner sites: an embeddable iframe with a state-specific (or national) countdown clock for the next scheduled execution, nationwide data on executions by year, etc.

4. The Marshall Project gets access to local expertise

“Some of this (data) we can get ourselves, but the most valuable thing we get is someone telling us what’s happening there,” Meagher said. With no reporters or sources in these states, The Marshall Project isn’t likely to get a call when news breaks. Collecting data is part of that, but they also get background on each case from partners who have been on the beat for, in some cases, 20-plus years.

5. The end result is a “network effect”

As essentially the curator of a nationwide pool of data, The Marshall Project is naturally better positioned to spot trends than any one local newsroom would. “There are eight different places working within their own sphere,” Meagher said. “When we roll them all together we can share it nationally, and highlight content they’re (creating) on case pages and state pages.” So, if there have been, say, three stories written about Ricky Gray in Virginia, there will be links back to stories in the Virginian-Pilot.

Where it could work better

The “network” works best when, as mentioned in our last post, reporting from local and national newsrooms flows both ways and leads to better, more collaborative reporting. That hasn’t happened yet, although folks involved think it’s possible.

“We’ve tried to use it as a springboard to other projects,” Meagher said. “We’ve had several of the partners on a call together to talk about ideas. It’s a good support group but hasn’t led to any shared reporting projects. We do want to find a way not just for everyone to pitch in data but to find stories for the whole group or some subset of the group. The hope is that it’s going to lead to the Panama Papers, some huge collaboration. But it’s a huge amount of work just to maintain the base level, you never quite get to the big pieces.”

The value of informal collaboration

And while collaboration across a network of partners is the ultimate goal, just the knowledge that there is a group — and associated calls and emails — have led to a type of less-formal collaboration and idea sharing.

The Next to Die relationship led to a broader co-reporting project between the Marshall Project and AL.com about the sentencing power of Alabama judges. And a conversation with their partner at the Tampa Bay Times led to this story about Florida’s unique law that allows juries to recommend the death penalty by a simple majority vote, which the Times reported on its own.

“When a story comes across (from one of the partners) we can spot trends and look at examples of other stories and keep up with what’s going on around the country,” Olsen said. “It’s inspiring to read what other people are doing.”

This piece was originally published by the Center for Cooperative Media at Montclair State University, and republished with permission.

____________________

Tim Griggs is an independent consultant and advisor to media companies (and others). He’s the former publisher of the Texas Tribune and former product and strategy executive at The New York Times. He can be reached by email (gunnertg@gmail.com) or via Twitter (@HeyTimGriggs).

Tim Griggs is an independent consultant and advisor to media companies (and others). He’s the former publisher of the Texas Tribune and former product and strategy executive at The New York Times. He can be reached by email (gunnertg@gmail.com) or via Twitter (@HeyTimGriggs).